17 Games In May: The 1916 New York Giants and the Best Road Trip Ever

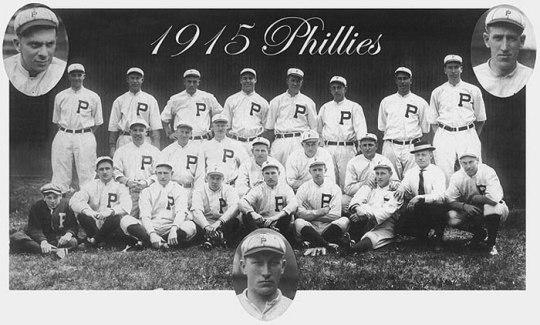

New York Giants Manager John McGraw and Philadelphia Phillies Manager Pat Moran, Opening Day at the Polo Grounds, April 20, 1916 (Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

I heard an interesting statistic the other day. The San Francisco Giants had just completed a 7-game road trip sweep, and the Giants were quick to note that is was their “longest road trip sweep since 1913.”

And I looked it up. It’s true. The 1913 New York Giants were in the middle of a 14-game winning streak when they won four in Philadelphia and four in Brooklyn.

But it’s not the best road trip the Giants have ever had. Not even close. And the reason for that is because of the way the baseball schedule was set-up for about 75 years. That reason is also known as: trains.

When trains were the best, fastest, and most reliable mode of transportation, the Major League Baseball schedule was designed so that teams routinely would be at home for 20 games or so, and away for 20 games or so. It was a matter of convenience. When the furthermost western team was St. Louis and trains were the fastest way to get there and back, there was no way the Giants could finish a series in St. Louis on a Thursday and start a series at home in New York against the Phillies the next day. But because this is the jet age, the Mets are doing exactly that in August.

The only way the Giants could have had an 8-game road trip 100 years ago- or 75- was to have the trip be in Philadelphia (across the river, essentially) and then in next borough, Brooklyn. Which is exactly what they did in 1913. Hell, they could have even slept in their own beds every night because it takes about 90 minutes to get from Philly to New York even today. (Remember, no lights meant every game was a day game that on non-doubleheader days started about 3 in the afternoon.)

It was 100 years ago this month that the Giants had the best road trip ever. They did not sweep the road trip, because that would have meant winning 21 games in a row. But they did just about the next best thing by winning the first 17.

That set a new major-league record for consecutive road wins, and it still stands, although the wrecking crew known as the 1984 Detroit Tigers tied them by also winning 17 straight on the road. But Sparky Anderson’s powerhouse did that over a month’s time, with no road trip lasting more than six games.

Starting May 9th, 1916, when they were 3-13 and in 8th (last place), they won four straight in Pittsburgh. After a day off for travel, they then won two in Chicago, had another day off to get to St. Louis, won four straight there, won three straight in Cincinnati, had a day off to get to the boroughs and won four straight against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field. New York was now 19-13, and even then was a game and a half out of first place, where Brooklyn sat. On May 30th the streak ended as New York lost the first game of a doubleheader in Philadelphia.

There are very few names on the Giants roster at the time that a casual baseball fan would recognize today. Obviously the manager is one, John McGraw. The 1st baseman was Fred Merkle, who more people know from the unfair characterization of him in the 1908 pennant race between the Giants and Cubs and the crucial game that ended with “Merkle’s Boner.”

The other is a pitcher by the name of Christy Mathewson. Merely one of the best players to ever step on a diamond. Matty was in his final months with the Giants, as he was trying to rebound from arm trouble that caused him to have a terrible 1915. Matty pitched in five of the 17 wins during the streak. He saved the first game, started the fourth, won the 10th with a complete game (his best game of the year), saved the 12th, and pitched another complete game for win number 17.

And depending on your knowledge of deadball baseball, you may also know of “Laughing” Larry Doyle and Benny Kauff. Doyle was a great star in the early 1910’s for the Giants, even winning the equivalent of the MVP in 1912, the Chalmers Award (as Chalmers made cars, the trophy was a new car).

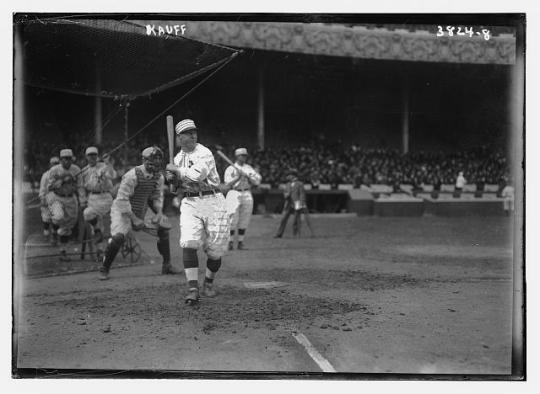

Benny Kauff, 1916 (via Bain Collection, Library of Congress)

Benny Kauff, meanwhile, was the biggest star of the Federal League, the last true challenge to the major leagues. Known as the “Ty Cobb of the Federal League” because Cobb was the best player in baseball at the time, Kauff was bought by the Giants in February of 1916 when the Feds finally officially collapsed. While the ballplayers being polarizing is thought of as a new development, Kauff (and Cobb, especially) did that 100 years ago. While no one could argue that Cobb was an all-timer (though that doesn’t excuse his actions), Benny believed the hype more than he lived up to it. Though he had good seasons with the Giants, he never approached his gaudy Federal League numbers. But Kauff lived large, trash-talking and dressing in flashy clothes, which then- and now- bothered the establishment. When baseball cleaned house after the Black Sox scandal of 1919, Kauff was suspended not for gambling, but because of his supposed involvement in a car theft ring. Though found not guilty in an actual legal trial, baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis never lifted Kauff’s suspension because he thought the trial was fixed and didn’t like Kauff’s attitude in general, one of many times the first Commish messed with people’s lives because he didn’t like them personally.

Back to May 1916, where the 17-game winning streak continues to be remarkable in several ways (aside from, you know, the winning 17-games straight part). First of all, I think more people nowadays are more astounded that road trips could even last 21 games. The longest road trips in the jet era so far have been the Montreal Expos in 1991 when a beam fell at Olympic Stadium forcing games to be moved, and the Houston Astros of 1992, with both teams spending 26 games on the road. While the Astros trip was scheduled, unlike the Expos, it was also because of a special circumstance. The Republican National Convention was at the Astrodome, their home park, that summer (likely because of Texan and then-sitting President George H. W. Bush- aka George 41), and required them to vacate for four weeks. Any road trip over 12 games nowadays is seen as an injustice. But like I explained up top, 20 game road trips were the norm for every team for at least the first half of the 20th century.

Second, the Giants weren’t in first place when the streak was over. In fact, the Giants never even touched first place in 1916. They lost their first game on April 12th, and the closest they got to first was the next day, when they evened their record at 1-1 and were part of a 6-way tie for second, and June 3rd, when they were also a half game out.

Third, it wasn’t even close to New York’s longest winning streak of the season. In September, the Giants set the all-time major league record by winning 26 games in a row.

All at home.

Hey, if you’re gonna be on the road for 20 games or more, sometimes you’re going to be at home for 20 games or more.

The Giants 26-game win streak, by the way, is deserving of much more than an afterthought, where it is in every baseball history I’ve seen. I’m working on fixing that. Stay tuned.